WTO: Australia successfully defends its implementation of the Services Domestic Regulation plurilateral in its GATS Schedule

Earlier this month, the Findings of the Arbitration initiated by India against Australia regarding Australia's implementation of the Services Domestic Regulation Joint Initiative (Services DR JI) were made public. This was an exciting development for me as it brings together the GATS, the plurilateral negotiations, and obscure procedure into one package.1

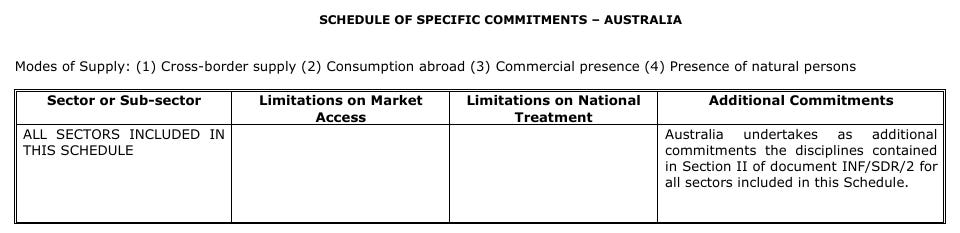

As expected, Australia was successful in the arbitration, meaning it can proceed to just cross-reference the Services DR JI paper in its GATS Schedule rather than copying and pasting in the entire document as India convinced others to do. The decision itself is relatively straightforward, without any major surprises. For those interested in how it played out, though, in this post I walk through some of the highlights (Peter Ungphakorn has also provided a good write-up of the arbitration that is worth a read).

India always had minimal chances of winning this arbitration (see some background here). GATS Article XXI and the associated arbitration procedures2 are focused on ensuring that modifications to GATS Schedules maintain a “general level of … commitments” that is not less favourable to trade and “compensatory adjustments” where amendments do take commitments backwards. India’s concern with the Services DR JI, however, was that its negotiation more broadly was not legal.3 India had also already accepted the substance of the Services DR JI being included in other WTO Members’ GATS Schedule, with some minor clarifications and a change of form. This made it difficult for India to argue that the content of the proposed modification to Australia’s GAT Schedule really changed the level of commitments or was less favourable to trade.

As an aside (and given my previous pleas for greater transparency in trade), I'll note that we don’t have the benefit of Australia or India’s submissions to see exactly how they argued their cases. However, the Working Procedures of the Arbitration Body do allow each party to disclose their statements to the public now that the Findings have been circulated. So, there's nothing stopping either party from doing the right thing and letting us see the documents now. Arguments over jurisdiction

At the outset, Australia had two wins and a loss on its jurisdictional arguments, knocking out two of India’s arguments but not being successful on having the entire request for arbitration rejected.

India had asked the Arbitration Body to decide upon its arguments that Australia’s proposed modification “violates the structural consistency of the GATS multilateral framework” and “undermines the single undertaking principle” (para. 3.53). However, the Arbitration Body agreed with Australia that neither of these matters are “benefits under the GATS within the meaning of Article XX:2(a)” and so found that India had not “demonstrated how or why a discourse on [these issues] … would contribute towards establishing whether compensatory adjustments would be warranted in this case” (para. 3.30). Thus, the Arbitration Body refused to consider these arguments.

Australia was not successful, though, on its broader attempt to have India’s entire request for arbitration rejected (para. 3.31). Australia argued that none of India’s concerns were about Australia’s overall levels of commitments or their favourability to trade (and in fact Australia’s modifications were entirely trade liberalising). As such, according to Australia, there was no issue or debate regarding a need for compensatory adjustments that the Arbitration Body could rule on.

The Arbitration Body disagreed with Australia on this - essentially saying that it had to decide for itself whether India’s benefits had been impacted and if there was a resulting need for compensatory adjustments. The Arbitration Body did, though, severely limit the scope of the matter it would consider (following its terms of reference) to:

3.31. … (i) examining the compensatory adjustments requested by India; and (ii) finding a resulting balance of rights and obligations which maintains a general level of mutually advantageous commitments not less favourable to trade than that provided for in GATS Schedules prior to the negotiations.

In doing so the Arbitration Body also emphasised that to succeed India had to not just show that its benefits under the GATS may be impacted but to also demonstrate that “its benefits under the GATS would be so affected as to alter the ‘level of mutually advantageous commitments’ resulting in a situation less favourable to trade”.

India was obviously hamstrung in its ability to do this given that (a) the Services DR JI clearly does not in any way reduce the participants’ levels of commitments or restrict trade, and (b) as noted above, India had accepted the substance of the Services DR JI being included in other WTO Members’ GATS Schedules (so at most this was a disagreement over form not substance).

Clarity and specificity of the proposed modifications

Before dealing with whether Australia’s proposed modifications impacted India’s benefits, the Arbitration Body decided it first had to consider whether Australia’s amended GATS Schedule was “sufficiently clear” to allow a comparison between it and Australia’s original commitments.4 The lack of “clarity and specificity” was also one of India’s arguments that its benefits under the GATS had been impacted (para. 3.53).

The three “clarity and specificity” arguments were:

First, India argued that cross-referencing to another document did not “reasonably communicate the substance of the commitments” (para. 3.32) and could result in the automatic incorporation of future amendments to the Services DR JI. The Arbitration Body rejected this argument, finding that the reference to “INF/SDR/2” clearly identified the document that was being incorporated at a specific point in time and that any future changes to Australia’s commitments would need to follow GATS Article XXI before becoming effective.

Second, India argued that cross-referencing to the Services DR JI “would create two separate regimes” (one for the Services DR JI commitments and the other for Australia’s existing GATS Schedule commitments) and “any conflict arising between the two regimes may not be reconciled effectively” (para. 3.38). However, India did not identify “any specific instance” where the modifications would actually conflict with existing commitments (despite the Arbitration Body’s invitation for India to do so). The Arbitration Body also agreed with Australia that as the modification concerned “Additional Commitments” under GATS Article XVIII these were necessarily distinct from and couldn’t conflict with Australia’s existing Market Access and National Treatment commitments.

Third, India argued that the drafting of the Services DR JI (particularly its use of the word ‘Member’ in various ways) could be read as creating new commitments for other WTO Members or make Australia’s new commitments more favourable for Services DR JI participants as compared to other WTO Members (in contravention of MFN) (para. 3.43).5 The Arbitration Body disagreed, noting that Additional Commitments only bind the Member that scheduled them, and that MFN treatment is a general obligation that cannot be modified via GATS Schedules (only by specific MFN Exemptions Lists). Australia also clarified the reading of its new commitments through a “‘without prejudice’ draft letter”.6 As a result, the Arbitration Body ultimately found that the modification was “sufficiently clear”.

Did the proposed modification restrict trade?

Resolving the above issues then allowed the Arbitration Body to turn to the heart of the matter - India’s argument that the proposed modifications “restricts trade in services rather than facilitating it” (para. 3.54).7 However, given that the Arbitration Body had essentially struck out India’s broader, systemic claims (around structural consistency and the single undertaking) and then found no issues around clarity and specificity, it dealt with this point very quickly. The Arbitration Body noted that “India had not identified any instance where the additional commitments referred to in the proposed modification would conflict with existing commitments in Australia’s Schedule” (para. 3.53). This was despite the Arbitration Body requesting specific examples from India.

Given all of the above, the Arbitration Body concluded that India had not demonstrated that the proposed modification would result in a situation less favourable to trade and thus found that no compensatory adjustments were warranted.

This was a fascinating little dispute given how small the stakes seemed for Australia but also how clear it was that India had so little to rely on to make out a claim for compensation.8

In the end, going through with the arbitration means that Australia saved itself the trouble of redoing its schedule and it also hasn’t had to acknowledge that its modification “does not create[s] a precedent for incorporating outcomes in the WTO, including from the Joint Statement Initiatives” (which was language India required the other participants include in their certification documentation). Although I’m not sure how useful this would actually be in practice, and I doubt this was a driving force behind defending the arbitration. Perhaps it really was just about the principle of what was being alleged (and the satisfaction of being in the right) that saw this through to conclusion.

Given what are apparently India’s true concerns regarding the plurilateral agreements, it would seem more appropriate for it to bring a dispute regarding the WTO Agreement itself rather than use these ancillary processes. This course of action - though - would obviously be a much more contentious on India’s part. India likely sees itself as being able to hold off the incorporation of the other Joint Statement Initiatives (JSIs) (on E-Commerce and the Investment Facilitation for Development Agreement) without resorting to this, as implementing these in schedules would require some radical changes to their content. Based on the latest General Council meeting, India’s strategy seems to be working. At that meeting, the incorporation of the two other JSIs into the WTO Agreement was blocked by a small number of WTO Members.

Full disclosure: I worked on the WTO Joint Statement Initiatives plurilateral negotiations for Australia, including the one that led to this arbitration (although I did not work on the arbitration itself). Nothing I post here breaches any confidences of course.

While none of India’s arguments on clarity and specific were accepted, presumably even if they had been India would still have needed to demonstrate that the lack of clarity “affected” India’s benefits.

This was an issue that India had other Services DR JI participants clarify when they modified their Schedules through notes in their request for certification of their amended Schedules.

It’s not clear to me why this letter was “draft” and particularly why it was “without prejudice”. The Arbitration Body also noted that Australia had made remarks similar to the content of the letter at the Working Party on Domestic Regulation and presumably the clarifications are not something Australia needs to reserve its right to resile from in the future.

This is one of the arguments where it would be great to see India’s actual submissions. There is also over two pages in the Findings discussing what “findings of the arbitration” mean as India attempted to restrict the circulation of the Findings on the basis of a somewhat strained reading of S/L/80 (see Section 3.5), which are a bad sign for my hope the submissions will be released any time soon.

I’m slightly disappointed there weren’t more creative arguments put forth against the modifications.