FTAs: Three points of interest from the India-EFTA Trade and Economic Partnership Agreement

India’s recent run of trade agreements continues, with its Trade and Economic Partnership Agreement with the European Free Trade Association (TEPA) getting signed last week. It is quite a ‘streamlined’ agreement, with the main text coming in at around 70 pages (as a comparison the Australia-India ECTA’s main text is around 116 pages). Within those 70 pages, though, there are some interesting elements (particularly in terms of India’s FTA practice). I’ve highlighted just three in this post.

First, there is a direct link between India’s preferential tariff commitments and the EFTA States increasing investment into India. I’ve previously posted on the ways in which governments convince each other to sign up to a trade agreement (in the context of IPEF), the TEPA now provides another more explicit model of the negotiations can go.1

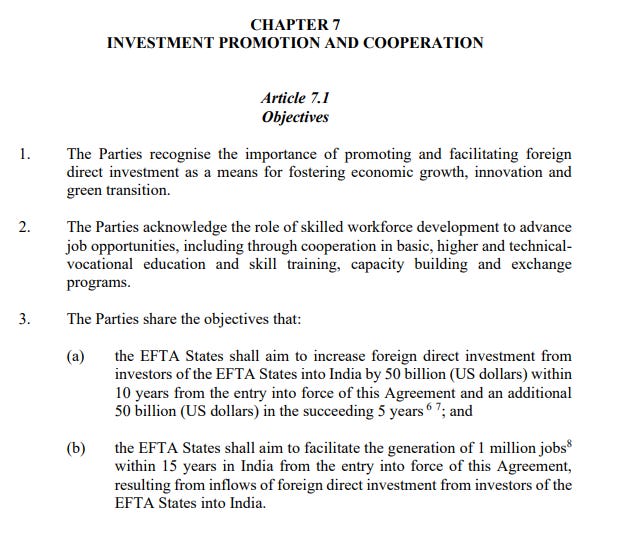

The EFTA States have agreed that they and India share the objective of “aiming to increase foreign direct investment [from EFTA States…] into India” by US$100 billion and to facilitate the creation of 1 million jobs in India over 15 years:2

This is accompanied by a linked obligation on the EFTA States in Article 7.2 to “promote foreign direct investments [from EFTA investors]… into India”.

While phrased as “shared objectives”, and though formal dispute settlement does not apply, the TEPA also includes a lengthy review and consultation mechanism for Articles 7.1 and 7.2. The result of that mechanism seems to be that if the shared objectives aren’t met and India considers that the EFTA States have not fulfilled their obligation to promote investments in Article 7.2, India is then able to ‘proportionately’ suspend its tariff concessions to “rebalance the concessions given”.

Based on my initial review, the mechanism appears to involve the following steps (and corrections are welcomed):

The Investment Sub-Committee reviews whether the shared objectives in Article 7.1 are achieved at the 5- and 15-year anniversaries of TEPA entering into force.

If the shared objectives have not been achieved within 15 years and “India considers that the EFTA States have not fulfilled the obligations to promote investments from investors of the EFTA States into India”, India can then request mandatory consultations within the Investment Sub-Committee to determine if the EFTA States have fulfilled their Article 7.2 obligation and to find a mutually satisfactory solution.

These consultations can take up to one year.3 If the matter is not resolved in that time it is referred to the TEPA’s Joint Committee, begins its own consultations. The Joint Committee has six months to resolve the matter, and if it can’t the matter is referred to Ministers.

Finally, if after six months of Ministerial-level consultation, either Party can request a “grace period” of three years. But once the grace period expires (assuming no mutually satisfactory solution is found and the shared objectives aren’t achieved in that time), India is able to “undertake temporary and proportionate remedial measures to rebalance the concessions given to the EFTA States in the Schedule of Commitments under the Chapter on Trade in Goods” (Article 7.8(1)).

The remedial measures must be temporary and if they continue beyond three years, any Party can request examination by the Joint Committee as to whether they should be modified or terminated. The Joint Committee must resolve the issue in six months or refer it to Ministers. There’s no time limit for Ministers resolving the issue, although if the remedial measures aren’t terminated the Joint Committee will keep examining them every two years following the same procedure.

To summarise all of the above: if EFTA investment into India has not increased by US$100 billion in 15 years’ time (or there aren’t 1 million new jobs created), and India considers the EFTA States haven’t done enough to promote investment into India, after around 4.5 years of consultations India can suspend its preferential tariff commitments. Technically the suspension has to be “proportionate to rebalance the concessions given”. Although working out what is proportionate would seem difficult given this involves comparing investment to goods trade. That said, with there being no recourse to dispute settlement, India may not be too worried about how precisely it will need to justify the particular remedial measures it takes.4

This whole set-up is also interesting as it is an example of a new form of ‘binding’ commitment. It’s not binding through traditional State-to-State dispute settlement. But the consultation mechanism and threat of remedial measures surely incentivises implementation/compliance (although working out whether or not the EFTA States ‘promoted’ foreign direct investments and the generation of jobs in India might not be straightforward).

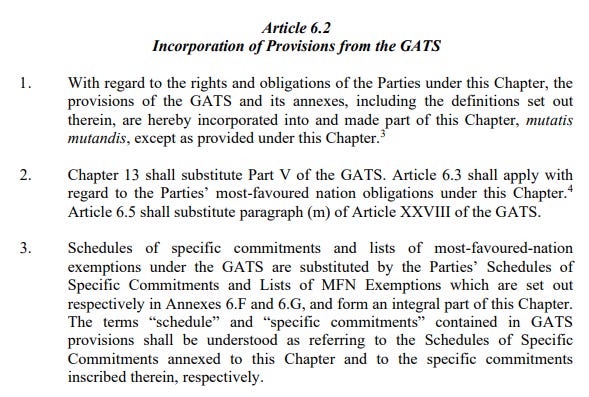

Second, TEPA’s Trade in Services Chapter is laser focused on market access. Instead of setting out its own architecture for services commitments, the Trade in Services Chapter opts to just incorporate the GATS and its annexes in their entirety into the agreement and make a few substitutions:

While in the past there have been more specific incorporation of certain GATS provisions or specific annexes, I haven’t seen this more expansive direct use of the whole of GATS in recent years. Usually, Parties want to make tweaks to improve on some of the now a few decades old GATS language or add some improvements. Here though, it looks like India and the EFTA States have just focused on improving their services market access commitments rather than services trade rules (although I haven’t examined the Services Annexes closely to work out the extent to which they add to the GATS rules).

It’s also interesting that the Trade in Services Chapter contains its own Most-Favoured-Nation (MFN) Article and MFN exemption lists, but that this appears to just lower the value of the MFN commitments. The MFN Article carves out all financial services, so goes backwards on the GATS in terms of overall MFN coverage. India also appears to have broader exemptions under TEPA as compared to under the GATS.5 I haven’t examined the EFTA States exemption lists, so it is also possible they offered some GATS-plus MFN commitments.

The two ‘improvements’ are that: (1) the MFN Article adds in an ability for a Party to request consideration of amending TEPA if the other Party enters into a trade agreement that gives better treatment in the future (a minor advantage compared to the GATS); and (2) TEPA has binding State-to-State dispute settlement, which may be of value until the WTO fixes it Appellate Body issues.

Finally, while Desiree LeClerq’s post on the IELP Blog digs into more of the detail of TEPA’s Trade and Sustainable Development Chapter (TSD Chapter), I’ll just note here that the TSD Chapter has a very broad security exception:

India has stuck relatively closely to the WTO-style security exceptions in many of its past trade agreements (although there are divergences and instances of broader language closer to the above being used). Indeed TEPA itself applies only the WTO security exceptions for its Goods and Services Chapters, suggesting there is greater concern of the TSD Chapter hampering security actions than market access commitments. In addition to this exception, the TSD Chapter also contains a dispute settlement carve-out - really doubling down on ensuring the chapter won’t impinge on policy sensitivities.

See also reports that Australia is offering technology transfers to convince India to lower tariffs in their current trade agreement negotiations.

Note the Article has lengthy footnotes defining what investment counts (i.e. only of investors of an EFTA State not investment “routed through EFTA States” by non-EFTA investors), and that the basis of the shared objectives is that they are linked to India’s future estimated nominal GDP growth being in line with its historic growth and the benefits of full implementation of TEPA from which “the Parties anticipate an outperformance margin on investment of 3 percentages points per year”.

The language on this is potentially ambiguous - Article 7.7(8) says the Investment Sub-Committee must “endeavour to settle issues within 60 days” and that the “period may be extended by no more than 1 year”. However, Article 7.7(10) then says if “after the 1 year period from the request of consultations…the matter remains unresolved” it is referred to the Joint Committee. I take Article 7.7(10) as the key time period.

Could the dispute settlement carve-out also mean EFTA States could argue that India can’t actually rely on Article 7.8 to violate its tariff commitments?

There’s also been some media coverage on the lack of India’s MFN commitments under TEPA compared to their agreement with Australia (full disclosure: I worked on that agreement for Australia, everything I write here represents my views only and doesn’t disclose any confidences). Australia’s agreement with India also doesn’t contain a carve-out from MFN for future trade agreements, which is in GATS and TEPA.

Terrific analysis. I suppose another example of a non-dispute settlement incentive to comply with a positive obligation is the WTO TFA which conditions developing country obligations on developed country assistance. I was tempted to add the UK-EU TCA’s rebalancing mechanism (and similar based on safeguards) but these are not linked to positive obligations (do X) but to negative ones (don’t do Y).